3 – Exiting the system

Reading time: 8 minutes.

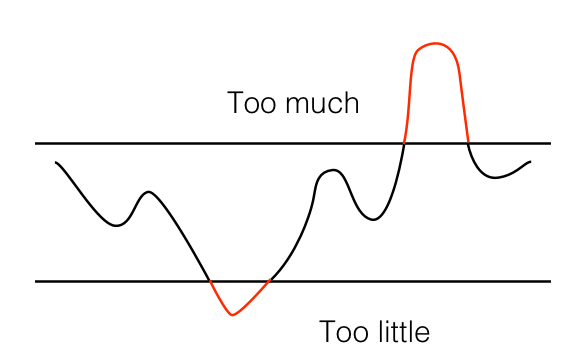

In the previous two chapters, I discussed the need to achieve alignment between what is good for us, our organization, and the planet. I also described two systems’ intersection, as when two elevators cross each other: one goes down (the existing system) while the other goes up (the emerging system).

I will now discuss how the exit from the system happens and where people stand regarding these two elevators, these two curves. What follows is deliberately general, so I recommend that you make as many connections as possible to your reality and the opportunities that this brings.

Like our reality, our position regarding the systems at hand is determined by where we focus our attention. I will deal with these cognitive aspects in a later chapter. In the previous chapter, I described how the system in place no longer knows how to manage its own complexity and is therefore plunged into chaos. In its flight forward, and to ensure its survival, this system requires our full attention. We see daily how our attention and our time are stretched beyond the limits of reason. That entails individual and collective consequences.

Every time we deviate from this system’s demands, it calls us to order and will not fail to make us pay for our escapades. Our daily life is full of rituals of obedience.

Schematically, two places determine our position in relation to the system: in or out. When one is “not in,” one is “out” or “beside.” Let’s see this in more detail.

Position 1 – Inside

“Inside,” people are still, voluntarily or not, hooked to the system. This position is the most comfortable because history justifies the system’s inertia, i.e., its tendency to maintain its direction and speed. It is also, of course, the most dangerous because it condemns us to follow the trajectory of this system.

Add the fear of change, of the unknown, of emptiness and failure that are often fed by the mainstream media, the temptation to look outside the current system, or even imagine that there might be an “elsewhere” can be reduced to zero. The justifications for remaining clinging to the past are innumerable.

There are all sorts of postures within them. I will isolate three main types, knowing that such categories are limiting and that we can pass, according to the circumstances, through one or the other. Whatever they are, the perspectives that lead to these positions are legitimate because they are related to what people perceive, what they can and want to see.

In the first position, people believe in the system and defend it. Some defend it to the point that they are willing to push the system to its extremes to get it back on track. They are well aware that there are problems, but their confidence in the structure gives them hope that solutions will be found. This posture often results in various forms of entrenchment and attempts at rationalization.

The second posture is that of doubt. People in this category are similar to the first, with the significant difference that they have begun to lose faith in the system in place to find the necessary solutions. This doubt often starts with a personal observation before being expressed and shared publicly. I will come back later on to the process of passage towards which this posture leads.

The third and final position is that of internal rebellion. Whether on a personal or collective basis, those who find themselves in this position clearly see the system’s inability to face its challenges and experience its violence. They express their frustration and anger. They demand accountability and answers, and they demand change. That is a difficult position, as the “traditional” means of attempting dialogue enormous efforts that are often not rewarded.

Moreover, these people may find themselves categorized negatively: the system quickly labels them with multiple degrading labels. The structures can easily associate a person in this position with all sorts of currents of thought that have nothing to do with where the person is located. It takes a good deal of courage to hold this position. In a way, this third position is like the “canary in the mine,” knowing that the “miners” are doing everything they can not to hear them and to suppress the warnings.

Again, these categories are not exclusive, and there are multiple variations. Also, depending on the situation, a person may find themselves in any of these postures.

Position 2 – Outside, elsewhere

These are people who are outside the existing system, at least “in their heads.” They are busy building and growing projects that are, by definition, outside the system. These people are in action. These are predominantly localized projects, but they touch all areas: education, agriculture, social, research, and new technologies. There are millions of such projects around the world, and their validity and actual or potential effectiveness will become clear as we discuss the notion of fractals in later chapters.

The system in place likes to believe that the people who work on these projects are a bunch of twenty-first-century hippies who have gone to take refuge in the countryside. Not so. Neither their appearance nor their behavior allow to recognize them. It is their actions that differentiate them. These people are working, each in their own way and with all the successes and failures that come with such an approach, to create a more sustainable world.

Also, the number of people devoting some or all of their time to these projects is constantly accelerating. Ten years ago, you probably didn’t know one of them, even by reputation. Today you probably know several of them personally and perhaps are already part of one yourself.

Position 3 – Outside, beside

Between “in” and “out” are the smugglers. Being “beside” the system allows one to function with it, but being, if not physically, at least cognitively and psychologically protected. Cognitive security allows one to consider the system in place as an external object, of which one is no longer a part. Psychological security is essential because it eliminates the fears that populate the system in place and contribute to ensure its continuity. To externalize the system in place, that is to say, to consider it as an object out of us and not in us, gives the opportunity not to undergo all that it undergoes, not to feel all that it feels.

Passers-by can understand the difficulties of the system without judging them with excessive severity. They are also clear about the necessity and potential of the “elsewhere” I just described. These facilitators help illuminate the potential of emerging systems. In the following chapters, we will see how they hone their posture and communication to participate in individual and collective change.

In the first chapter, I referred to the frog in the kettle, a systemic archetype in which the poor beast ends up cooked without realizing it because the temperature has risen insensitively. A species’ ability (and therefore of a system) to survive in its environment is linked to its ability to adapt to changes in that environment. When the environment changes (in this case, deteriorates) beyond a certain threshold or speed, the species can no longer adapt and disappears.

By environment, we mean the physical environment and the organizational environment, and therefore the political, economic, and social aspects. What seems to me even more essential is the cognitive environment: how we process the information available.

The last decades show that our reality is more and more made of chaos. Since no one is attracted to chaos, it is easy to seek comfort in what already exists, even if it is not ideal. Seeking reassurance in a chaotic system also plunges us into chaos. The solution is obvious: we must jump out of the pot. But we must be aware that we are in a pot, that its temperature is rising and that it is possible to jump out.

Unawareness or denial of these possibilities is unacceptable because it leads us directly to tragic situations, but it is understandable. On a personal level, it is helpful to understand how we decide to change. Here it comes from within, from ourselves, not from an external event as Elisabeth Kübler-Ross describes it in the grief curve.

Recognizing: tipping point

An expression says that people change out of inspiration or desperation. Inspiration usually comes from the outside. We can think, for example, of charismatic leaders. Most of those who currently have a large audience speak of “tinkering” with the system in place. Very few open up to emerging horizons. Finally, those who do are automatically subject to criticism and campaigns of disinformation and denigration.

Fortunately, inspiration coming from outside can also be acquired by cultivating oneself, by reading, by going to sources of information and knowledge that pass “under the radar” of the system in place.

Inspiration is then internalized. It comes from within. People who are lucky enough or who have made the effort to go down this path become leaders while taking advantage of the fact that they are, once again, “under the radar.”

Desperation follows a different path. As we will see below, most of those who change for this reason probably didn’t even think about it six months before. Very often, these people had found an acceptable (in)comfort in the existing system. It was clear that this system did not provide real solutions, but it was there and offered various forms of reassurance that one had chosen to believe. Trust still held.

For these people, the change was like an hourglass turning over. Each grain that runs out is a doubt, a disappointment, a frustration, a promise not kept, one more goal not reached, one more crisis not managed. And when the flow starts, there comes a moment when it cannot be stopped. Then comes the moment of the tipping point.

At this precise moment, it becomes evident that the system in place will not solve the problems it is facing. That is the moment when, quite naturally, we start to look “elsewhere.” The emergency opens the door to opportunities.

This shift happens one brain at a time. But when it brings hope, change is contagious. If there is little or nothing left to hope for from the existing change, and if the emerging phenomena show signs of viability and vitality, the polarity becomes obvious. People are talking, sometimes in hushed tones, but they are talking, contributing to the exponential of change. I will devote a whole chapter to exponentials, but let’s just say that the curve is practically flat and initially undetectable. Now let’s look at this shift in detail. That will be useful for you as well as for those around you.

The first phase of the decided change is to “recognize” that the change is necessary. That is not just a mental process. Many people know that they need to stop smoking or exercise. But the head, the mind, is not enough.

Recognizing is done with our whole being. The moment of recognition takes a few seconds. These seconds bring out the obvious: the current situation is unacceptable and must be changed. To reach this point where reality imposes itself on us, we must have taken the necessary time to accumulate enough information that shows the impossibility of remaining in the present state. I have just mentioned an hourglass, but you can also think of a scale with trays: at some point, the weight of the information tips the scale.

This process, therefore, requires taking into account external signals. But you will understand that the frog I mentioned before is not necessarily interested in these signals, especially when it is trapped in a kettle-system (and I will not venture to consider that there could be a lid on the pot).

Like attention-grabbing, unbridled activity is also a great way to hide inertia. At worst, for those stuck in this first position, inside the system, even if the discomfort is extreme, there is no recognition, therefore no desire to change.

Acceptance: towards autonomy

Recognition leads to the second phase, acceptance. Once we have recognized the need to change, serious business begins. Indeed, no longer being so attached to the system in place, one cognitively leaves its grip and arrives at the second point, between the two curves. But it is not as simple as walking through a door.

Indeed, our environment is still almost entirely occupied by the old system. Its hold is firm, and it is vital to keep a cool head. That means, for example, that we must keep in mind that what surrounds us is not “the” reality, but “a” reality. While evolving in this reality, we become capable of considering other realities. This phase of acceptance leads to autonomy.

Once again, a snap of the finger will not be enough. Symbolically, it is the crossing of the desert. You know where you came from and where you can no longer be, but you are not yet clear on where you want to be and how to get there. It is, therefore, a period of uncertainty, and there are traps.

Autonomy is being built. During this desert crossing, you have to be careful not to be isolated. At the same time, you have to be careful with the people you meet. For example, it is not helpful to spend too much time talking about your journey with people who are decidedly hooked on the existing system and want everyone to “stay in it.” I’ll come back to this in the chapter on cognitive aspects, but let’s just say that one of the excuses for staying stuck in the current system is to take inventory of failed attempts.

On the other hand, it is good to share your experiences and feelings (your doubts, your joys, your victories, your fears) with those who are following the same process. The challenge here is to know who to trust and on what subjects. This approach contributes to the personal development of each person. Empowerment occurs at the individual level before becoming collective. Experiments and attempts are increasingly made in groups and, as in nature, those that work are reproduced and extended. Eventually, this leads to convergences that trigger mobilization.

In any case, it is essential to remember that everyone is entitled to his or her own opinion and that no opinion should be categorized in any way, either way. Human nature is much more complex than one opinion or another.

By going “outside,” there is another trap that I will call cocooning. You are “out,” but you don’t want to “in.” It is like recreating a matrix that is no longer dysfunctional but illusory. It is necessary to take care of oneself and to have moments of comfort. But this should not be an excuse to constantly share “inspirational texts” or videos that make us feel good or confirm our beliefs with others who are equally disconnected from reality. The empowerment phase is active. It is not a good idea to skate in place.

Because this phase is active, and I mentioned this in the previous chapter, it is primarily devoted to experimentation. How do you know what works if you don’t try? It requires persistence and a lot of creativity. We must therefore know how to take risks, including concerning our belief systems. Maybe everything is not so impossible, achieving results may not require massive efforts, and it may be possible to have fun while contributing, etc.

One of the first tangible and positive signals that we are getting out of the current system is when we start asking questions about the sensemaking of what we are doing (I have already talked about sensemaking, and I will come back to it several times). It is also helpful to share what we see, without judgment, but by putting our reality down and taking our place and responsibility.

There is a difference between taking risks and putting yourself in danger. Know how to discern when and where taking a risk becomes putting yourself in danger and vice versa. Empowerment sharpens the senses.

Further: going beyond

As far as creativity is concerned, it is a gift that you have to accept and manage. By accepting, you have to stop those automatic excuses like “I’m not creative,” which just closes the door on your potential for reasons that are most often external and long forgotten. Managing your creativity is a bit like managing a geyser. You don’t necessarily know when it will come.

The American singer Tom Waits tells us that one day while driving on a highway in Los Angeles, he was suddenly, as he says: “visited by his muse” with ideas for magnificent creations. Alone at the wheel of his car, unable to take notes, he exclaimed aloud: “Can’t you see I’m driving here? Come back later and wait until I’ve parked.” Exiting the current system opens up new horizons and multiple possibilities, and it’s essential to be able to ride this wave of creativity with a modicum of serenity.

I just thus evoked several positions between the system at the end of its life in which we must continue to evolve but to which we no longer belong, and the emerging system that carries the future. The stakes and risks are considerable, but do we have a choice? Yes, of course, we have a choice. To say that we don’t have a choice is a choice. And choosing to get better is a beautiful choice, but not as simple as it sounds.

Our actions must lead to and fuel the upward curve. That is not a wish or a program. It is a description, made from a point outside the existing system, of what is going on. From now on, I’m going to place us in this position next to the system.

That is the bridge builders’ position. These are the passers-by, those who illuminate the potential of emerging systems. We are ready to consider what role we should play when we find ourselves between these two curves. We will see that in the following article.

—

To go further:

– On Elisabeth Kübler-Ross: the Swiss-American psychiatrist developed in the late 1960s a model describing the phases of mourning following the announcement of a terminal illness diagnosis. This model, which is very well known and used in all sorts of fields related to change, describes five stages: denial, anger, negotiation, depression, acceptance. As I mentioned in the article’s body, these are changes imposed by external events, not deliberately decided.

– On the tipping point: in systemic coaching, change is sometimes described as an “edge” tipping point. There are many ways to move from the edge with which one is familiar to the other. One of the basic notions is that there is inherent wisdom in exploring the “other side.”

– On seeing and listening: Otto Scharmer, professor at MIT and author of multiple books on Theory U. He also launched the concept of Ulabs that allows us to redefine the way we perceive reality, anchor ourselves in our potential of the present moment, and co-create resilient futures.

– On the fact that our environment is almost entirely occupied by the system still in place: Matrix is an excellent metaphor for this (otherwise, the movie would not have been as successful).

– On failed attempts: In my consulting work, I sometimes have to ask those who fall into the “we tried and it didn’t work” trap if they have children. Then I ask them what would have happened if, when their child learned to walk, after ten unsuccessful attempts to stand, they would have said, “you can’t do it, let it go, just keep on crawling.” We often have to ask what the system “wants” to bring out, not what we can do with our resources.